This post is gently adapted from a text message exchange with a good Christian friend who wanted to select a Bible for her children. I was honored that she reached out to me, as I surmised she had some consternation with using/not using the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible. The following is a gently adapted version of what I sent her with additional modifications for my blog audience. Without further ado, let’s look at Bible translations.

While I wasn’t raised in the church or with any regular Bible reading, I’m one who was told the KJV was the only correct Bible translation. My mother emphasized the “Authorized Version,” probably based on what she had heard in her time in various worship assemblies. To the extent possible and based on having a consistent text, I tend to use the KJV for preaching, when reading the Psalms, or when the primary recipients are KJV-only Christians. (I won’t deep dive into KJV-only believers. I love them as brothers and understand their passion, but I don’t think KJV-only is a correct position to hold. In this regard, I am not KJV-only, but I could perhaps be viewed as “KJV priority.”)

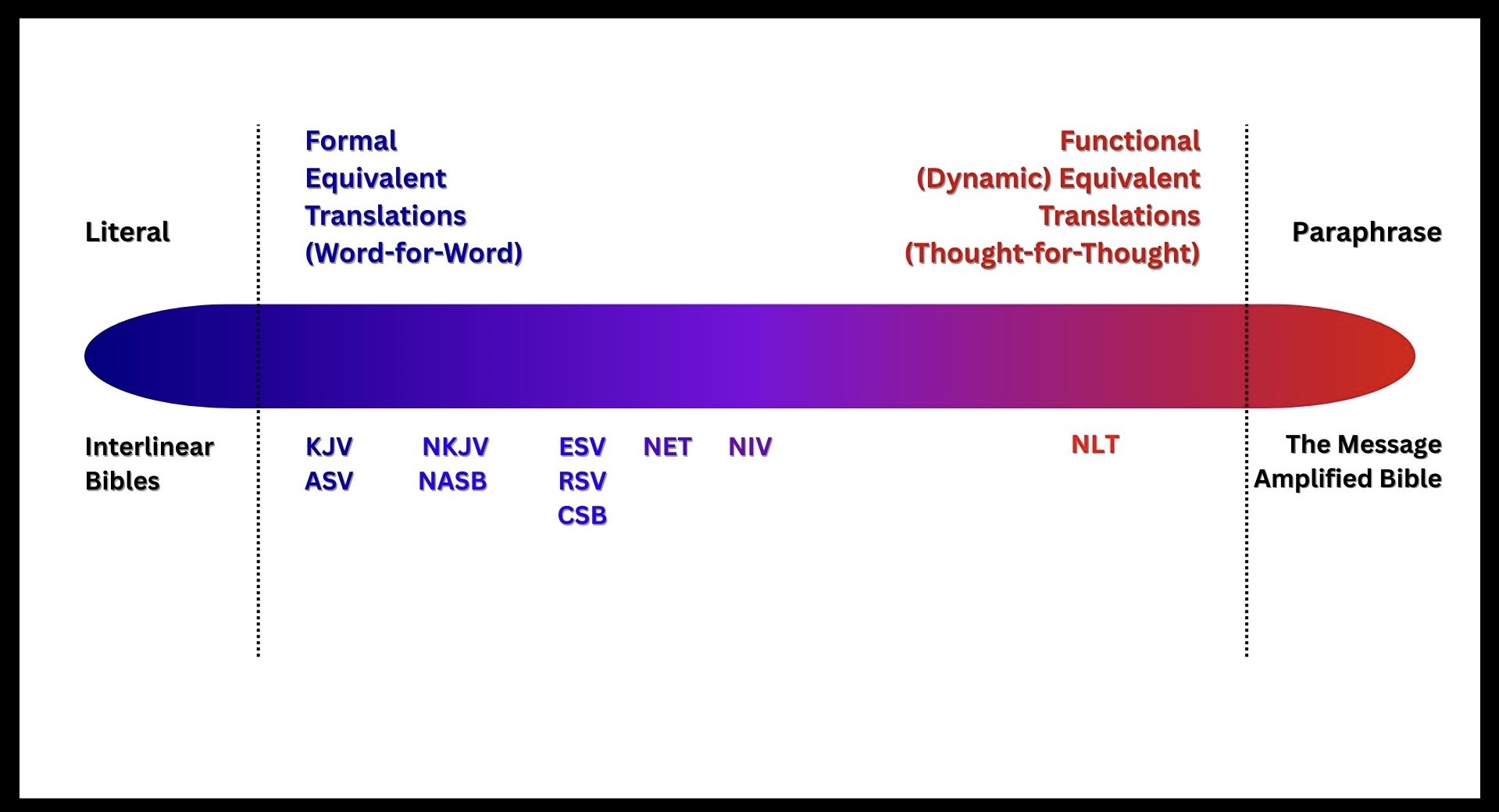

Regarding translations, other than KJV, I tend to use five other translations: English Standard Version (ESV), Christian Standard Bible (CSB), New American Standard Bible (NASB 1995), NET (New English Translation), and New King James Version (NKJV; in that order). I usually reference any of those translations, depending on the need and audience. In addition, I also use other orthodox Bible translations for reference, study, or to satisfy curiosity (i.e., New International Version – NIV, New Living Translation – NLT, Amplified – AMP), but I don’t typically use them formally for preaching/teaching.

Without going too deep into textual differences, the KJV is based on two collections of manuscripts: (1) the Textus Receptus (TR, meaning “Received Text”) for the New Testament, and (2) the Masorectic Text (MT) for the Old Testament.

The TR was based on the best available manuscripts around the time the KJV was compiled. Erasmus and other KJV scholars used those collections of NT manuscripts to compile the first widely-circulated and authorized-by-the-king version of the Bible in English (c. 1611 AD). Since that time, other manuscript collections have been discovered and compiled, some dating back to the First Century, etched on papyrus, and other manuscript copies that are much older than the ones the KJV scholars used. (Dr. Daniel Wallace runs this organization which maintains high resolution photo preserved NT manuscript copies: Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts -CSNTM)

While modern Bible translations use contemporary English, aside from the NKJV, the other modern translations I referenced are based on a different collection of NT manuscripts, not merely the TR. Those other translations and their translation committees believe the best available manuscript collections are different from the TR (The ESV uses Novum Testamentum Graece for example). They also may use the Septuagint (LXX, the Greek translation of the OT) and other manuscript traditions.

Ultimately, absent learning ancient Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic, the use of a variety of translations is probably the best way to get a feel for the Scriptures’ original language. I encourage readers to use regularly any Bible translations that are orthodox and not paraphrase or paraphrase-adjacent (i.e., AMP and NLT respectively). I also encourage readers that the best Bible translation is an orthodox one they’ll actually read.

Additional Considerations

Children. It’s easier for children to learn from more modern translations rather than the KJV or American Standard Version (ASV). At the same time, if they learn to read the KJV, they’ll always be able to read other translations. Should a parent start with the KJV and their child continue to struggle grasping grasp the KJV and its archaic wooden language (e.g., “conversation” meaning “conduct” or “peradvendture” meaning “perhaps”), I recommend using another version like the NKJV or, if the parent is open to other modern translations, the ESV or CSB.

Translations and Truth. Although there are differences between KJV/NKJV and modern Bible translations due to their underlying manuscript traditions, those differing manuscripts are within 99% accurate of each other, which shows God’s preservation of truth throughout the ages. Where there are manuscript differences (whose differences are often due to scribal errors in copying or writing comments in the margins), they don’t change any fundamental Christian doctrine. A man can learn who Jesus is and find salvation in Him using the any of the modern orthodox Bible translations..